The ground often gives way and leaves little footing; maybe that is why I am so buoyant.

Life is full of events — you may have noticed — both fortunate and otherwise.

The essential teaching of Stoicism seems to be that, with a mind of discipline intent on right perception, those events we sometimes find so unfortunate can nonetheless be turned to gold.

What’s more, it doesn’t make much sense to take ourselves so seriously. After all, what are we taking seriously anyway? It takes calm and quiet to look inward, and here is where what we think is ourselves often turns out to be only a passing thought like some cloud in the sky.

I was smitten, a boy of fifteen, enamored with a girl I had just met.

It was late summer, 2007. Thinking back now, I suppose I might have been wondering then if I was falling in love.

We had a week to enjoy together before she went home. That’s what we thought. When a few people at camp got sick, it didn’t make any headlines. It didn’t take long for that to change.

We all took a surprise crash course lesson in what an outbreak of highly contagious disease can look like.

A few dozen became ill. More would suffer if it wasn’t shutdown.

So it was shutdown.

After only a few days of this much anticipated week at camp, it was over.

Worse, this girl I liked so much was now on her way home, on her way to another state, and the only place I was going was Sad Town.

At age fifteen, that week was my last chance to be a camper before aging out. There was going to be a closing ceremony and everything. I was going to learn to sail. I was going to meet girls.

I was excited.

Sure enough, I enrolled in my sailing class (think very small boats). I was paired with a boy four years younger than me, and that was cool, because he was cool.

And sure enough, I saw a girl I wanted to talk to on the first day, did, and was smitten.

Then it was over.

Dad picked me up. The drive home was long enough for me to stare out the window a while, the forests and lakes of the area passing by. All my mind saw was this person I liked so much and how I didn’t know if I would ever see them again.

When we arrived home, I passed in through the doorway with my emotions obviously not beaming, my eyes maybe a little puffy, and my dad made a remark to my mom from behind me in the garage, as though he were introducing me (and maybe forewarning her).

Ever the cool operator, he said:

“He’s not a happy camper.”

How many of us are happy campers right now?

We all had plans. I don’t think anyone has gone unscathed through this pandemic.

Back in 2007, I thought I was going to get to know this person at camp.

Before the pandemic, I thought I would have no trouble living my life, taking on my life’s work — at least, not the pandemic sort of trouble.

I think most people thought this.

We were wrong.

The truth — hard as it may be to our minds that have been so dulled by longstanding oscillations between being coddled and shocked in the western milieu — the truth is that the pandemic didn’t need to be a surprise.

For some, this ongoing disaster is utterly unsurprising. It’s a white swan event, not the rare black swan that so many claimed in the early days (with their shallow verbiage, borrowing terms from the Risk Doctor without understanding them).

That’s the point: infrequent as pandemics of this sort may be, they are practically inevitable without taking adequate measures to prevent them, which we haven’t. The way we have patterned the everyday life of our species, combined with explosive incompetence with risk and complexity at every level of society — we have forged for ourselves a guaranteed baseline of pandemic risk. And similar risks of other ‘normal accidents’. Over time, such risks become realities.

We should not be surprised.

We should be disappointed.

The people charged with addressing such risks have been neutered by an ambient culture of anti-intellectualism, ceaseless manufacture of controversy, and a default to greed and bad faith at the highest levels.

It’s almost just as well. Seems they wouldn’t have been up to the task anyway, as both the WHO and various national CDC organizations have reliably demonstrated a lack of know-how when it comes to complex risk.

Think about how the US officials were advising against masks.

Recall that the WHO declared early on that there was “no evidence of human-to-human transmission,” even as Wuhan was days away from a brutal lockdown.

We should not wait for confirmatory evidence of such risks. We should ask ourselves, Could this situation be explained as the germ of runaway complex risk?

The match-to-the-tinderbox quality of our global travel patterns and other pandemic risk factors has been highlighted by more than a few people in recent decades. Failing to take heed has cost us dearly.

We may not always anticipate when or exactly how the ground will fall out from beneath us, but we can always anticipate that it will happen, somehow and sometime, to all of us, and in this way of recognition, we can start to find peace of a higher order.

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate my dad’s perhaps unwitting Stoic qualities. With a cancer that seemed to indicate the end being nigh, I think the worst of it that he let on was how uncomfortable he was in the confined spaces that the treatments required.

That was years ago too.

There is plenty I am unaware of there, and, honestly, I hope there was only scant emotional repression — rather, I hope he embraced them that he might let them go. I don’t know as well as I might like. Perhaps I am idealizing it. But I can think of many other times where his character shone through.

Maybe he was not interested in all the ways that some might have liked him to be, but when I think of my dad, I do see him as disinterested in the ways you would want a man to be disinterested. I recall walking upstairs to the first floor one time, on a night when we were the only ones around for the evening, and at just the same time he was entering the same hall. He had some sort of accident, and with his thumb halfway off, he said calmly something like, “Ev, I’m going to have to get to the hospital. Be sure the dog gets out and has water.”

He wasn’t quivering about it. He was just doing what had to get done.

I appreciate that.

I appreciate seeing that.

No doubt it played some part, however small, in my ability to calmly and properly clean some awful wounds to a friend’s face several years later, one where there were some tissues opened up that shouldn’t have been.

She took some jagged gravel to the face, hitting the ground headfirst from a five or six foot fall.

It was past midnight. We were in the wilderness and some distance from the hospital.

The next day, I woke up in a mutual friend’s car after that long night. We had got her to the emergency room eventually.

I must have smiled, because this mutual friend told me the doctors said they were impressed and couldn’t have prepared her any better. I got to drop her off to her family knowing that, half-asleep though I was.

With some of the risks in the world, though we should seek to understand them deeply, it’s as though we were adult children still deluded with an image of our parents as immortal, failing to prepare in even the most basic and commonsense ways for their inevitable death. What’s more, the parents suffer the same delusion. When it happens, things fall apart more painfully than they needed to.

(Thankfully my parents have no such delusions.)

Crazy as it may sound, we are getting off easy with this one — the pandemic, I mean. The next virus could certainly be much worse. There is nothing absolute to prohibit the emergence of more dangerous viruses.

We should use this time to deeply improve our relationship to such risks.

When I went back to camp at age sixteen, not as a camper, but as an employee, I had no training. The year of the viral outbreak at camp, when I lamented losing proximity to the cute girl who did my hair at the picnic tables and looked at me like I wasn’t used to being looked at, that was the year — the week — that I was supposed to be trained as a Junior Counselor. Like everything else, that class was cut short shortly after it started.

I only went to camp for that one foreshortened week of the last summer, so I arrived for my new Junior Counselor position with only my wits and observation to serve me — again, no training.

Fine.

Trouble was, the “senior” counselor to whom I was assigned as an underling had the same credentials as me, which is to say, none. He was my superior on the basis of age seniority only, not experience or skill. In the first minutes around this guy, it was clear I was in for a challenge. A year older, he was a Boy Scout who knew it, who took it a little too seriously. For example, he argued with the camp director on day one, “I know how to use my knife. I’m a Boy Scout. This should except me from the ‘no knives’ rule.”

Long story short, he immediately alienated people on contact. Greeting the arriving campers, it was me assuring parents. As I remember, he was piddling about nearby as I got our cabin’s campers settled; that, or he was being inappropriate-on-demand with them.

So just as my last week as a camper shuttered unexpectedly and abruptly, I was now a Junior Counselor looking after a dozen young boys and one old one who was supposed to be the leader of the pack. The anticipated on-the-job training turned out to include exercises in damage control.

That was the first couple of days, which was all the time he needed to teach our campers how to most effectively inflict pain on others (males) with the method he called “monkey grabbing peach”, otherwise known as grabbing someone’s scrotum and twisting it really hard.

He was let go, with five days left in the week.

I was now in charge of a dozen campers in our cabin, with no experience and no training.

(Later that year, with a few more weeks under my belt, I would look after a cabin filled to the brim with 25 kids, thankfully all of them rather disciplined pre-Olympian gymnasts, but that’s something else.)

The world is a lot like this now. We have incompetent leadership that should be ousted. We have people to care for, often with no idea how. And it doesn’t matter: we still need to get the job done, everyday.

And in many ways, we aren’t. This is more than a cabin of kids, after all.

After my counseling debut, reluctantly at first then wholeheartedly embracing my surprise position, I went on to work as a counselor every week that summer (except girls’ week, when I just washed dishes).

We can get the hang of things and do well. We can even do this with the complex systems and risks that imperil us so gravely today. This is true even and perhaps especially when we seem to lose our footing.

“… by going out of your mind you will come to your senses.”

— Alan Watts

We can’t, however, improve our lot if we are convinced it is an impossible feat, that we aren’t even ready to get ready, or that we are alone and uniquely challenged by life, unable to share our (common) burdens with others.

I took a lot of inspiration from my older brother at the time, captain of our cross-country team in the fall prior to my first summer as counselor, and indeed counselor of my own cabin (albeit for only a few days). It wasn’t any particular technique, rather a spirit of inclusivity, patience, and disciplined fun-loving that I sought to carry on in his absence at the camp.

So I did.

So can we.

When we observe disinterestedly the flows of our lives, we can release the sense that we need to force anything to fit our expectations, and we can work with it, play with it, and find that it is always changing anyway. With this, we can also refrain from the type of naïve interventions that exacerbate our woes.

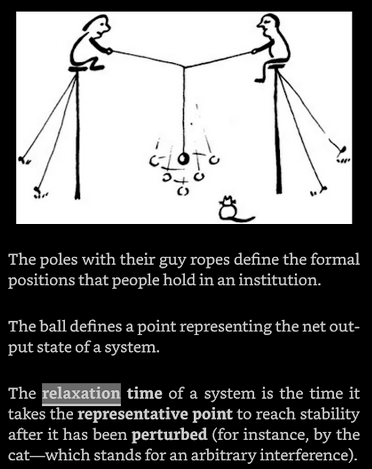

In systems, there is something called a relaxation period. We need these.

The thing to do now is to empower youth, not merely to better fit our expectations of them, but to play an active role in cultivating their critical faculties now with the benefit of heritage generated then.

Short of any new longevity miracles (which I admit do not seem too farfetched), the kids have more skin in the game than we do. They will live longer in this accelerating downward spiral that we seem to have setup for ourselves. It seems the least we could do is give them the best tools our heritage has to offer in actually addressing these global grand challenges of ours.

Complexity- and risk literacy are key among these elements of heritage to be maintained, as is systems theory. That much I know for sure. How can we understand and appropriately engage a truly complex world if we never pay any mind to methodically address complexity?

I should say now, the boy who I sailed with — I mentioned he was four years younger than me at least, when I was fifteen. That said, I had no experience sailing. Nonetheless, at age eleven, this boy was capable of coordinating the two of us on a sailboat, such that we nearly won our race. Perhaps even more impressive is how he coordinated us to right the boat when — I’m sure it was something I did — we capsized it.

What is the saying, age earns no value except through thought and discipline?

So we see that it is possible.

The youth today which, to some, can seem so chaotic in and of themselves, are actually hungry for responsibility, and not mere play responsibility, but real responsibility, and the tools to be competent in carrying out that charge.

There are ways we can help them do this, and we should.

— Evan M. Driscoll

August 27, 2020

Toronto